— Suzy Subways, Editor, Solidarity Project

November 2007 • Issue 7

Rumor has it that this World AIDS Day, December 1, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will announce that its estimated number of new HIV infections in the United States each year is higher than 40,000 for the first time since the late 90s – and it may be much higher. Meanwhile, in May, the CDC scaled back its previous goal of reducing annual new HIV infections in half to reducing them by only 10% a year. Is the government giving up on us? Instead of budget cuts that pit our communities against each other, why not add money for interventions that we already know are effective but have no federal funding streams, like syringe exchange and comprehensive sex education? What about studying new ways to fight the epidemic?

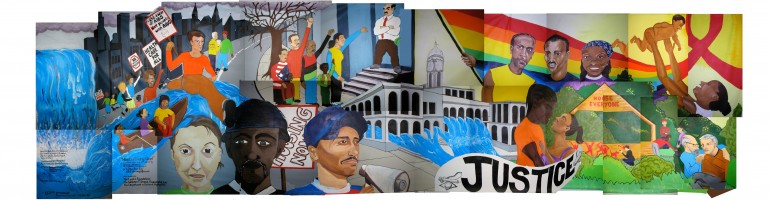

The Prevention Justice Mobilization (PJM), initiated by CHAMP in collaboration with SisterLove, the Georgia Prevention Justice Alliance, the Harm Reduction Coalition, the National Women and AIDS Collective, the New York State Black Gay Network, ACT UP Philadelphia, the Center for HIV Law and Policy, and AIDS Foundation of Chicago, is a dynamic force of activists from many communities. We are starting a new conversation in our AIDS service organizations, social justice circles, support groups and homes, and we are telling the CDC at its annual conference in Atlanta in December: We are not going to allow ourselves, as individuals and groups at risk, to be blamed for the consequences of government failures to prevent HIV. To end this epidemic, we have to change the way this country works.

“When people change and systems do not, HIV still thrives,” explains Dázon Dixon Diallo, MPH, a lead organizer of the Prevention Justice Mobilization and founder of SisterLove, based in Atlanta, the first and largest women’s AIDS organization in the Southeast. “We’ve been working under this assumption that HIV transmission is about individual risk behavior, and that’s where all of our resources and our best thinking have gone. But what’s missing from that is an understanding that HIV happens in a larger context. You can be vulnerable to HIV just because of who you are in the world. If you are poor, a person of color, LGBT, disabled, homeless, mentally ill, or dealing with substance abuse, injustices also exacerbate the transmission of HIV. Where are the resources to address those injustices?”

People in groups with higher HIV rates are often no more likely to engage in risk behaviors such as unprotected sex than other groups. But the disparities are just getting worse. Black women today are 23 times more likely to have AIDS than white women, and Latinas are five times more likely. Among white men who have sex with men (MSM), HIV rates have reached 21%, while 46% of Black MSM are HIV positive. Among Black transgender women, the rate is 56%.

There’s a sense that our communities are supposed to accept these disparities, and that AIDS has become one of many chronic poverty issues that we’re expected to see as individual failures – so stigmatized that it’s painful to even talk about them. In the 80s and 90s, poor women were blamed for needing welfare when they had no other options. The stigma perpetuated by the rhetoric and welfare reform allowed social programs to be cut, resulting in even fewer options for women – like the option to demand that your man use a condom if you depend on him to pay the rent.

Dr. Adaora Adimora, associate professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina, presented her research on the root causes of disparities in HIV rates at a congressional briefing last year. She said, “The usual response to this suggestion is to sort of shrug and say, ‘Well, we can’t do anything. We can’t change poverty and racism.’ As long as we continue to accept the status quo, we need to acknowledge that we’re actually just accepting racial disparities and disease rates. Racial disparity and HIV rates in the United States is a major civil rights issue, and it is, in fact, a major human rights issue.”

It’s tough to follow the complex ways that racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, anti-immigrant hysteria and other systems of oppression work together to increase HIV risk. Part of prevention justice is demanding more research to find out how this happens and how to change it. Our communities may be stigmatized, but our lives matter. HIV prevention programs are not handouts from the government – they are reparations, a redistribution of wealth, only a beginning of what’s needed to end the AIDS epidemic and the systemic injustice that fuels it.

This issue of Solidarity Project spotlights just a few of the many people and groups that are building the Prevention Justice Mobilization. Some are new to activism; some are longtime organizers finding new ways to make moves for what’s right. All can inspire us.